Babygirl offers a nuanced, emotionally-driven perspective on the complex relationship between Romy and Samuel. At its core, the movie explores themes of self-acceptance, framed around an erotic thriller plot. The film centers on Romy, a CEO at a tech company, who finds herself emotionally restless despite living a seemingly ideal life. Played by Nicole Kidman, Romy’s frustrations are not just personal, and this internal conflict propels her towards Samuel, an intern who reveals an understanding of her long-repressed desires.

The film gradually builds up to an affair between Romy and Samuel, and while their intense connection poses a threat to Romy’s career and family, it also offers her a chance to break free from her current life. Though Babygirl unfolds as an erotic thriller, it isn’t simply about the physical aspects of the affair but is also deeply rooted in Romy’s journey toward self-discovery. Her interactions with Samuel ultimately catalyze emotional growth, culminating in a surprisingly tender and emotionally impactful conclusion.

Babygirl Ending Explained

Samuel and Romy (Image via Getty)

Romy’s journey toward an affair with Samuel is sparked by her growing dissatisfaction with her personal and professional life. At the start of Babygirl , Romy’s unhappiness is evident. Despite a successful career and a loving family, she is consumed by feelings of dissatisfaction. The intrigue around Samuel, who appears confident and unbothered by Romy’s position, begins as an outlet for Romy’s frustrations. As she admits to her husband Jacob later on, part of the allure of the affair is the high stakes involved—she is risking everything, which adds a thrilling dimension to her otherwise mundane life.

Romy’s connection with Samuel is both physical and emotional. His casual but dominant nature contrasts sharply with the controlled persona Romy adopts in her work and family life. Samuel offers Romy an escape from the facade she maintains, allowing her to be honest about her desires without judgment. This dynamic speaks to Romy’s need for liberation from the expectations placed upon her, ultimately setting the stage for the intense affair that follows.

Romy’s Childhood and Her Repressed Desires

Romy’s struggles with sexual frustration and her attraction to domination themes are explored through flashbacks and conversations in the film. She reveals that these desires have been a part of her since childhood, though she has kept them hidden, particularly from her husband Jacob. Throughout the film, Romy tries to reconcile her repressed fantasies with her current reality. In the early scenes, she masturbates to domination-themed pornography, hinting at a deeper conflict she is unwilling to confront.

Her emotional journey in Babygirl involves confronting and embracing these desires, with Samuel catalyzing change. The affair between Romy and Samuel is consensual, and Samuel is careful to ensure both parties are comfortable. Over time, Romy learns to communicate her feelings openly, especially with Jacob. This marks a significant step in her emotional evolution, as she stops hiding behind pretenses and starts owning her desires.

Romy and Samuel (Image via Getty)

Revelation of the Affair

Initially, Romy and Samuel manage to keep their affair under wraps. Samuel’s visits to Romy’s home don’t immediately alert her husband or daughters to the truth. Moreover, their relationship is disguised as a professional mentorship. However, as the film progresses, multiple characters begin to uncover the truth. The most emotional revelation comes when Romy admits the affair to Jacob, who is enraged that she put everything at risk for something so reckless.

The film’s third act is largely about the fallout from this revelation. Jacob confronts Romy, and they navigate the fallout from their marriage. Additionally, Romy’s assistant, Esme, discovers the affair and is frustrated by Romy’s abuse of power in the same way many male employers do. There’s also an implication that someone higher up at Romy’s company knows about the relationship, which complicates her professional life further.

Does Samuel Love Romy?

The film subtly explores Samuel’s feelings for Romy. At first, Samuel’s interest seems to be casual and driven by his ability to dominate, as evidenced by his nonchalant interactions with Romy. He initially sets boundaries around their relationship, refusing to complicate things, and seems content with his more casual connections, like with Esme. However, as the film progresses, Samuel’s affection for Romy becomes more apparent. When he takes her to an underground club, he opens up more emotionally, showing tenderness and affection that wasn’t present in their earlier meetings.

By the end of the film, Samuel has developed feelings for Romy, but he understands the importance of her family and her career. Samuel’s decision to end the affair, despite his love for her, reflects his understanding of the larger consequences of their relationship. This bittersweet conclusion encapsulates the theme of the film, as both characters must navigate their desires and the realities of their lives.

Samuel and Romy (Image via Getty)

Romy’s Relationship with Her Daughter, Isabel

An intriguing subplot in Babygirl involves Romy’s relationship with her daughter, Isabel, who starts as a rebellious teenager. Isabel is initially shown as distant and at odds with her mother. However, as Romy’s affair with Samuel deepens, she and Isabel develop a surprising understanding of each other. Their relationship evolves when Romy catches Isabel cheating on her girlfriend. In a poignant scene, they share a cigarette and discuss the nature of relationships, with Isabel revealing her affair was “just for fun.”

This dynamic between Romy and Isabel serves as a mirror of Romy’s own experiences. As Romy comes to terms with her affair, she sees parallels between her daughter’s choices and her own. This understanding leads to a deeper bond between them, and by the end of the film, Romy has reconciled her emotions and is in a better place both with Isabel and Jacob.

The Core Message of Babygirl

At its heart, Babygirl is about Romy’s journey toward self-acceptance. The affair with Samuel serves as a pivotal moment in Romy’s life, allowing her to embrace her desires and confront her internal struggles. Samuel, while a central figure in the story, acts more as a catalyst for Romy’s emotional growth rather than a fully fleshed-out character. The real evolution occurs within Romy, as she learns to be honest with herself and her family.

The film’s ending suggests that Romy can have it all—her career, her family, and the kind of sexual relationship she desires—without sacrificing the life she has built. By embracing her true self, Romy finds a sense of fulfillment and peace, reinforcing Babygirl ’s central theme of self-acceptance. Ultimately, the film portrays the possibility of reconciling one’s desires with the responsibilities of life, offering a compelling emotional resolution.

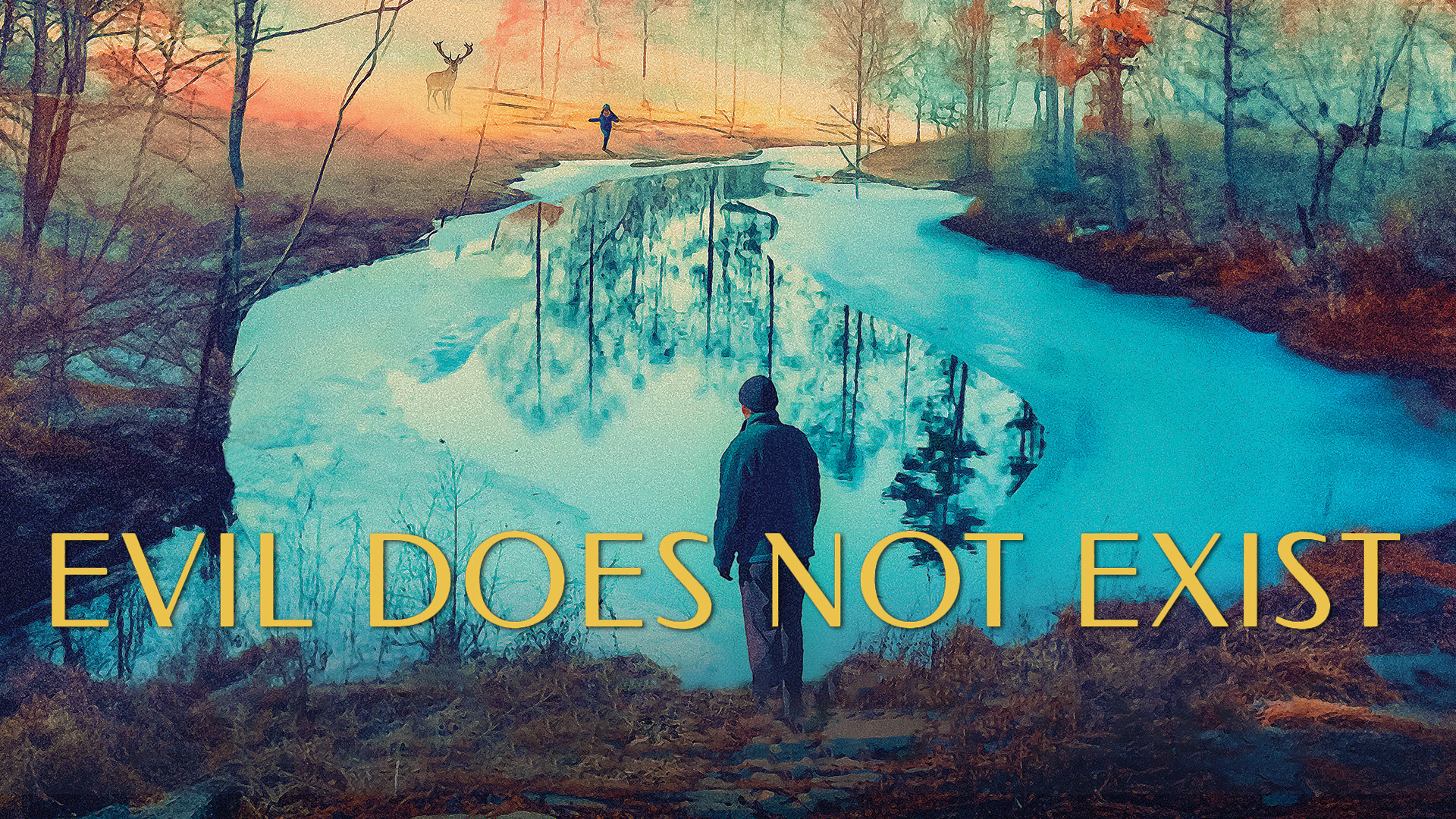

Ryûsuke Hamaguchi’s Evil Does Not Exist immediately sparks conversations, thanks to its intriguing title and the events that unfold. Even before watching the film, the title alone raises questions. The phrase “Evil Does Not Exist” feels like an unlikely statement that contradicts how most people perceive the world. The deeper one gets into the film, the more these themes unfold, especially with the characters’ actions that cause harm to others. However, it’s the ending that leaves the biggest mark, provoking a whirlwind of debate and multiple interpretations.

Hamaguchi is known for his complex, thought-provoking endings, as seen in his Best Picture Oscar nominee Drive My Car . That film concludes with a long, reflective sequence, leaving much of its meaning to be pondered over time. Similarly, Evil Does Not Exist brings a sharp focus on a 20-minute scene involving a community’s objections to a planned luxury development. The abrupt and surprising ending of Evil Does Not Exist leaves viewers questioning what they just witnessed, stirring up even more questions about its meaning and intentions.

Evil Does Not Exist Ending Explained

Evil Does Not Exist (Image via Getty)

The film is set in Mizubiki, a small rural village under threat of disruption from developers planning a luxury camping site. During a town hall meeting, locals present well-thought-out objections to the project, impressing the developers, Takahashi and Mayuzumi. However, Takahashi and Mayuzumi discover that their boss isn’t concerned with the project’s sustainability or profitability. Instead, his main focus is to secure pandemic-era development grants by meeting a looming deadline.

As the developers continue their work, they connect with Takumi, a widower from Mizubiki, raising his young daughter Hana on his own. Takumi is a quiet man deeply connected to nature, a fact that intrigues Takahashi, who envies him and dreams of living a similar life. However, the peaceful atmosphere is disrupted when Hana goes missing. The town rallies together in search of her, and eventually, Takumi and Takahashi find her lying in a field, having been attacked by a wounded deer.

In a stunning moment, Takumi turns on Takahashi, strangling him before grabbing Hana’s body and running. Takahashi stumbles through the field before falling and lying motionless. The film leaves viewers wondering whether Takahashi or Hana is dead, and Hamaguchi himself admits that he intended to keep these elements open for interpretation. The director wanted the film’s abrupt ending to spark reflection and conversation about the characters and their choices leading up to that moment.

Takumi’s Motivations Explained

To better understand Takumi’s sudden attack on Takahashi, Hamaguchi points to a conversation earlier in the film. Takumi tells the visitors that wounded deer, although usually harmless, can become dangerous when they’re in pain, especially when they’re protecting their young. This notion serves as a metaphor for Takumi himself, who is deeply wounded both by the impending destruction of his community and the harm inflicted on his daughter, partly due to his neglect.

Takumi, like the injured deer, lashes out irrationally. His violent reaction is not aimed at the source of his pain but rather at the nearest target: Takahashi. As the film unfolds, it becomes clear that Takumi has struggled with his role as a father. Hana’s presence in the woods alone, which leads to her encounter with the deer, highlights his failure as a caregiver. Takumi’s attack on Takahashi can be interpreted as an expression of desperation, an emotional breakdown triggered by the realization of his past mistakes.

Hamguchi aims to offer a nuanced portrayal of Takumi’s emotions and actions. The director hopes that viewers will return to the film after the surprising ending to reassess the character’s earlier behavior. He explains that each character in the film has a rich, untold life beyond what’s shown on screen. Even if Takumi’s actions seem extreme, Hamaguchi wants audiences to feel that, given Takumi’s circumstances, his behavior could be understood.

Takumi (Image via Getty)

The director views the ending as an invitation for deeper reflection. By leaving certain elements ambiguous, he encourages viewers to reexamine the narrative and challenge their interpretations of what they have just seen. This kind of open-ended conclusion allows for multiple readings, enriching the experience and offering room for debate.

Understanding Takumi’s Extreme Response

Hamaguchi compares Takumi’s behavior to a woman’s choice in Asako I & II , where a character’s seemingly misguided decision helps her understand herself. Similarly, Takumi’s violent act stems from his inner turmoil, frustration with his fatherly failures, and his struggle to protect his community. His attack on Takahashi challenges expectations and defends his community against outsiders.

Hamaguchi views Takumi’s actions as an instinctive, emotional response, much like an animal’s defense when cornered. The director invites viewers to interpret Takumi’s motivations in their way, leaving room for different conclusions.

The Significance of the Film’s Title

The title Evil Does Not Exist carries deep thematic weight. Originally intended as a short film, the title emerged before the full story was conceived. Hamaguchi recounts visiting the area where composer Eiko Ishibashi creates her music, surrounded by the tranquil beauty of nature. He realized that despite the harsh, cold winter he didn’t feel the presence of evil. The title was born from this observation and reflects a worldview that sees nature as neutral, not inherently malicious.

Hamaguchi acknowledges that human actions within society complicate this perspective. While nature itself is not evil, human behavior, especially in urban environments, can often be harmful. The developer in the film, who brings destruction for personal gain, embodies this human capacity for harm. Yet, Hamaguchi suggests that such choices, driven by desire, are also part of nature. This nuanced understanding of the film’s title challenges viewers to reconsider their assumptions about morality, good, and evil.

Takumi (Image via Getty)

Opening Scene and Its Connection to the Film’s Themes

The film opens with a four-minute tracking shot, looking upward at trees in a slow, steady motion. While this shot may seem disconnected from the film’s conclusion, it foreshadows the themes of perspective and understanding that Hamaguchi aims to explore. The camera’s controlled movement, which humans cannot replicate, offers a unique viewpoint that emphasizes the role of perspective in interpreting the world around us.

This opening shot, paired with the title, reinforces the film’s central message: nature is not inherently evil, and understanding the world requires a careful examination of one’s surroundings and experiences. As the film progresses, this concept of perspective becomes increasingly important, urging the audience to question their initial judgments and explore the complexities of the characters’ actions and choices.